|

RSN October 2013Contents

Annual Meeting News

|

Brain, Stomach, and SoulCara Anthony and Elise Amel, University of St. Thomas

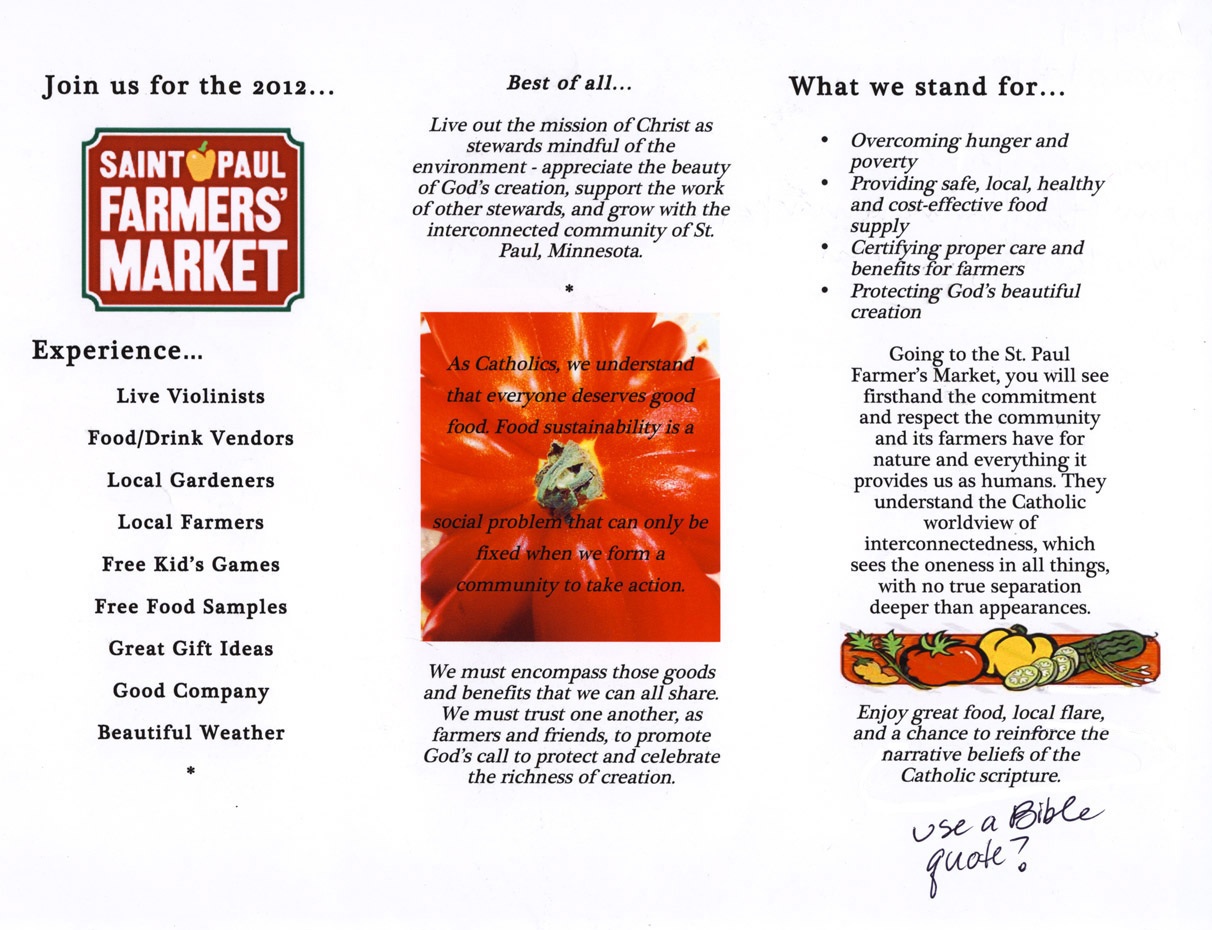

Elise Amel has a PhD in industrial-organizational psychology from Purdue University and has been teaching at the University of St. Thomas, Minnesota since 1997. She is a professor of psychology and former director of Environmental Studies who has earned awards for leadership in both service-learning and undergraduate research mentoring. Amel has co-developed and co-taught many sustainability-infused courses including "Psychology of Sustainability, Theology and the Environment"; a philosophy course about environmental problem-solving called "Save the Humans!"; and a MBA course, "Managing Sustainability." She has conducted conservation psychology research since 2004, culminating in dozens of peer-reviewed conference papers, journal publications, and a book chapter. She has successfully led efforts at the University of St. Thomas to provide faculty development opportunities for infusing sustainability across the curriculum: creating a sustainability coordinator position, conducting ecological footprint analyses, signing the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment, and including sustainability as a strategic priority. Psychological “Framing” in a Theology ClassroomWhat does daily diet have to do with faith? Is the way I eat a meal sustainable and meaningful? Are my food choices consistent with my religious values? These are the kinds of questions students grapple with through our team-taught, upper-level course that fulfills a core requirement in theology at the University of St. Thomas. At this level, courses are designed to give students an interdisciplinary perspective or to address a pressing social issue. “Theology & the Environment” does both, since we address the issue of food sustainability through the lenses of both theology and conservation psychology. A good amount of grappling with this complex, interdisciplinary issue occurs through a series of short academic journal entries that account for about half the graded work of the semester. In the journals, students interpret experiences such as growing a basil plant, shopping for and cooking a meal, or visiting an urban farm in light of both theological and psychological concepts they have learned in class. Although many of the individual entries do not require students to write about both psychology and theology, one assignment in particular requires students to employ their knowledge of an important psychological concept to communicate effectively with a religious group. This entry is due near the end of the course, after students have had practice integrating material and just when the markets in Minnesota are offering the first local produce of the season. Students visit a local farmers’ market and, afterward, create an advertising flyer that appeals to a specific religious group—Buddhist, Jewish, or Christian—drawing on values, beliefs, and practices of the religion to encourage members to visit a farmers’ market. The psychological approach we emphasize in this assignment is called "framing an issue." Framing an issue in terms of beliefs and values that are important to a particular group is not the same as distortion or spin. Rather, framing calls attention to the most salient aspects of the issue for a specific audience. In course readings, students have already seen that certain religious beliefs, values, and practices overlap significantly with environmental outlooks. In order to create an effective poster for the farmers’ market, students need to know what the most relevant beliefs or values are that might help members of a religion see the connection between their worldview and buying locally grown food direct from the farmer. We encourage students to get creative with the assignment, and they do, incorporating images and creating slogans that function as framing devices—the specific elements that create the frame for the issue. For example, students who choose to create a flyer for Buddhists might refer to the “middle path,” which is the ideal of a moderate lifestyle avoiding both excess and poverty. They might evoke Jewish understandings of justice for laborers, or a Catholic vision of food as sacramental. Collaboration as “Iterative Praxiology”Two pedagogical concerns motivated us to create this assignment. First, this course has a lot of parts to coordinate—psychology, environmental sustainability, and three world religions. We chose to focus on food sustainability since food is such a fundamental element of everyone’s experience and plays important roles in the religions we study in the course. But we still needed to help students integrate psychology and theology—to see and experience the ways that humans can simultaneously act as both psychological and religious beings. Creating the flyer brings all the elements of the course together into a practical, problem-solving action. This leads to our second pedagogical concern: the relationship between theology and psychology that we want to model in the classroom. Would we try to harmonize the two disciplines as much as possible? What about potential areas of conflict? Fortunately, we found an approach that maximizes the cooperative elements of our classroom endeavor without losing each discipline’s distinctiveness. We adopted a pedagogical method from University of Portland professors Russell Butkus and Steven Kolmes. Butkus, a theologian, and Kolmes, a biologist, developed what they call the “Iterative Praxiological Method,” which is “the collaborative attempt to address a complex problem, utilizing scientific and theological-ethical analysis, with the aim of proposing ethical solutions and policy guidelines” (Butkus and Kolmes 2008). Instead of directly inquiring about the relationship between theology and a scientific discipline, both disciplines focus on a common problem: ecological sustainability. The method is iterative because it cycles repeatedly through four steps that can be summarized in the following way:

While this method was developed for a theology-natural science pairing, we adopted it for theology-social science, and it can certainly work for other disciplinary pairings. The farmers’ market flyer emphasizes steps two through four of the Iterative Praxiological Method. Utilizing the psychological theory of framing issues, students evoked core ethical values of a religion to tangibly address one aspect of a complex problem: the need to change the way we eat. The Benefits of InterdisciplinarityStrategic interdisciplinarity has helped us to model constructive collaboration between two disciplines that sometimes fail to connect with each other. We do not pretend that the instructors (or students) share identical worldviews, but we show how our shared desire for a safe and sustainable food system can bring different kinds of people together in ways that respect their various identities. Cooperating on approaches to common social problems also enables students to see the necessity of integrated learning. No one discipline is going to solve complex social challenges—we need all the wisdom and knowledge we can muster to resolve our current ecological problems. Team teaching also allows different students to connect with the course in different ways. Whether their primary interest is psychology, theology, or environmental studies, students are likely to find something that motivates them. Such variety can be a liability as well; anyone planning to team-teach has to make clear to students how to bring the two disciplines into dialogue with each other. The first version of our course had so many different elements to juggle that most students never connected them effectively. We alleviated this problem by providing a clear road map for the course, with assignments available weeks or months in advance of due dates. We assigned two ungraded journal entries to give students time and practice with this novel assignment and to adjust to instructors’ expectations. Nearly every class, we took a moment to “check in” on where we were in the Iterative Praxiological cycle, and to review how the day’s activities contributed to the successful completion of one or more future assignments. When returning assignments to students, we reminded them of what they had accomplished with each bit of work. We also learned not to sacrifice our own best teaching strategies in order to create a generic shared classroom style. For example, each instructor has different ways of leading students through difficult readings, and we do well to retain our best practices. This course would probably be different if it were not the third required theology course at a Catholic university. By the time students enroll in this course, they already have some knowledge of Christianity in general and of Catholicism in particular. This allows us to quickly review some topics, and to spend more time on other, less familiar ones. In other contexts, it might be necessary to study just one religion or to otherwise simplify the topics. And no matter what kind of interdisciplinary team teaching you try, you will never be able to “cover” your standard topics with the same thoroughness and depth as a single-discipline course. The benefits, however, make team teaching worth it. Too often, academic courses in theology end up being a history of ideas. Psychology has helped this course to move away from the trap of seeing religions only as cognitive belief systems, and to instead see them more as comprehensive schools of living. Students get to see how people succeed or fail in living out their religious commitment—and begin to understand why they succeed or fail.

Suggested ResourcesNext article |

Cara Anthony holds a PhD in systematic theology from Boston College and has been teaching at the University of St. Thomas, Minnesota since 2001. She is an associate professor of theology and current director of Environmental Studies. Her research focuses on the intersection of Christian spirituality, theology, and social issues. Her most recent essay is “Trinity, Community and Social Transformation,” which draws on Wendell Berry’s vision of local communities as resource for embodying Trinitarian Christian life. She has team-taught with Elise Amel for four years, and is currently developing her course "Theology and the Environment" to team-teach with a faculty member from Geology. Cara is currently co-writing a book for young adults on the Bible and evolution.

Cara Anthony holds a PhD in systematic theology from Boston College and has been teaching at the University of St. Thomas, Minnesota since 2001. She is an associate professor of theology and current director of Environmental Studies. Her research focuses on the intersection of Christian spirituality, theology, and social issues. Her most recent essay is “Trinity, Community and Social Transformation,” which draws on Wendell Berry’s vision of local communities as resource for embodying Trinitarian Christian life. She has team-taught with Elise Amel for four years, and is currently developing her course "Theology and the Environment" to team-teach with a faculty member from Geology. Cara is currently co-writing a book for young adults on the Bible and evolution.